Wine sounds like a reasonably simple beverage to make. You take some grape juice, let it ferment, and you have a delicious drink. But from GPS machines in the vineyards to Vinolok glass closures and Reverse Osmosis machines, there is always new technology making an impact on the wine industry - even if wine lovers might not be aware of the changes when they sip their glass of Shiraz.

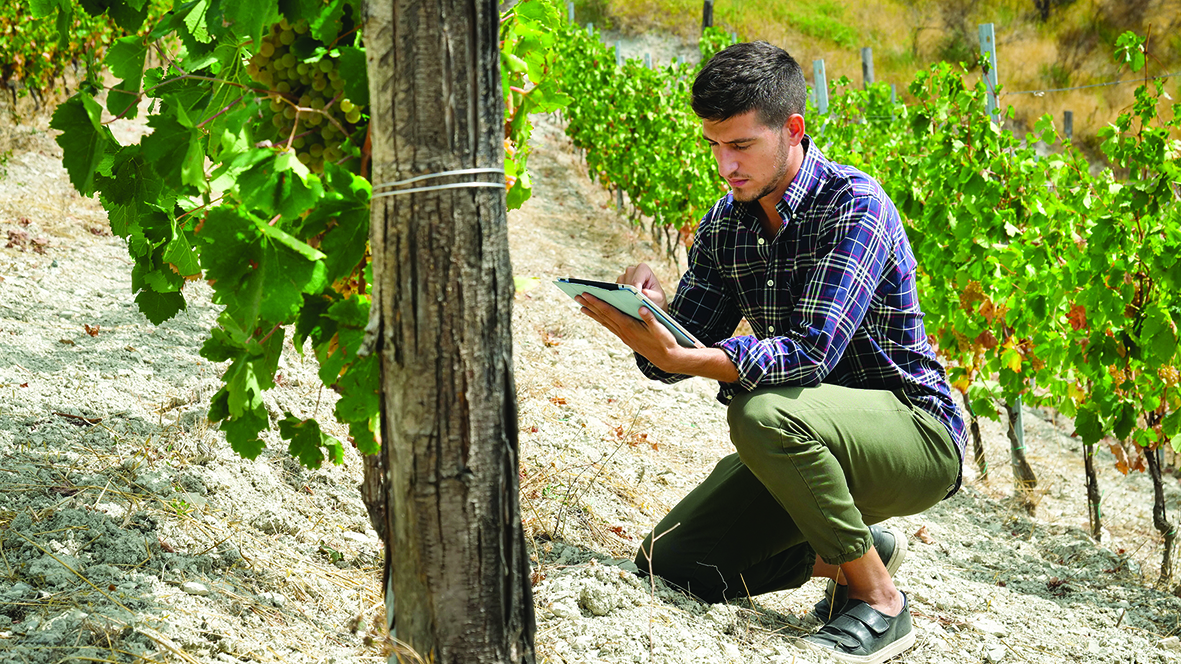

Researchers and wine scientists play vital roles in the wine business, which is continually looking for cutting-edge ideas and innovations both in the vineyard and in the winery.

Recently retired New Zealand wine scientist Dr. Mike Trought, who worked for Villa Maria Wines and at Lincoln University, recently underlined the many aspects of wine science he has undertaken in his career; from bird behaviour in vineyards to irrigation, yield predictions and canopy management. “Wine science is about trying to anticipate the future,” said Trought. “Today’s problems have to be solved with today’s information. Tomorrow’s problems have to be worked on today."

Recently retired New Zealand wine scientist Dr. Mike Trought, who worked for Villa Maria Wines and at Lincoln University, recently underlined the many aspects of wine science he has undertaken in his career; from bird behaviour in vineyards to irrigation, yield predictions and canopy management. “Wine science is about trying to anticipate the future,” said Trought. “Today’s problems have to be solved with today’s information. Tomorrow’s problems have to be worked on today."

"The New Zealand wine industry holds a special place in the world, which we are all passionate about. Our industry is like a grapevine, it needs to be nurtured and cared for to grow and remain healthy, for all great wines start in the vineyard.”

The Australian wine industry holds a technical conference every three years that looks at various research and technical innovations. It incorporates WineTech – the Australian Wine Industry Trade Exhibition, Australia’s premier exhibition of wine technology, equipment and services featuring winemaking and vineyard equipment, materials and associated services. In the past, innovation and technology have played an essential role in the success of the Australian wine industry.

Think refrigeration in wineries, tank infrastructure, and Stelvin screw caps. Now a new generation of sensor - driven viticulture tools is giving grape growers the ability to monitor and measure their vines like never before. Remote sensors with the ability to detect everything from how much water a plant is storing to how much light is falling on the ripening grape are revealing valuable information to growers.

Precision viticulture sees data collected via aerial images, either utilizing satellites or,

more commonly, flying an aeroplane or a drone over the vineyards, or the use of yield monitors. These devices are attached to harvesters and, when used with GPS, enable yield maps to be generated. Typically, the areas with the heaviest yields are of lower quality than those with the lower yields.

more commonly, flying an aeroplane or a drone over the vineyards, or the use of yield monitors. These devices are attached to harvesters and, when used with GPS, enable yield maps to be generated. Typically, the areas with the heaviest yields are of lower quality than those with the lower yields.Winemaker Peter Caldwell, who has worked in Australia and New Zealand and currently heads the Dalrymple operation in Tasmania’s Tamar Valley, says there is constant technological innovation within the wine industry. “Technology is probably more evident in mainstream wines,” says Caldwell, pointing to the use of micro-oxygenation, a process which softens tannins.

After it is in the bottle, oxygen is wine’s enemy, but by adding oxygen during key parts of the fermentation process, winemakers can improve a wine’s flavour and texture. Introduced in the mid-1990s, and a vital tool for larger producers is the Reverse Osmosis machine, which addresses the excess alcohol that results from high sugar levels in grapes.

In RO, the wine passes through a filter that blocks colours, tannins, and, flavours. The colourless and tasteless water and alcohol mixture are distilled to separate the alcohol from the water. The water is then recombined with the color, flavor, and tannins. The result: a small batch of wine with reduced alcohol. This small batch is usually blended back into the rest of the wine, thereby diluting the alcohol without losing any of the flavour elements.

“The main use of the RO machine is to find a sweet spot for a wine,” says Caldwell. The Pellenc company attracted a lot of interest with a mechanical harvester that has fruit-sorting capabilities. Pellenc’s Selectiv system is not only a mechanical harvester, but it also destems and removes material other than grapes.

After it is in the bottle, oxygen is wine’s enemy, but by adding oxygen during key parts of the fermentation process, winemakers can improve a wine’s flavour and texture. Introduced in the mid-1990s, and a vital tool for larger producers is the Reverse Osmosis machine, which addresses the excess alcohol that results from high sugar levels in grapes.

In RO, the wine passes through a filter that blocks colours, tannins, and, flavours. The colourless and tasteless water and alcohol mixture are distilled to separate the alcohol from the water. The water is then recombined with the color, flavor, and tannins. The result: a small batch of wine with reduced alcohol. This small batch is usually blended back into the rest of the wine, thereby diluting the alcohol without losing any of the flavour elements.

“The main use of the RO machine is to find a sweet spot for a wine,” says Caldwell. The Pellenc company attracted a lot of interest with a mechanical harvester that has fruit-sorting capabilities. Pellenc’s Selectiv system is not only a mechanical harvester, but it also destems and removes material other than grapes.

There are also machines that can be used to automatically time functions in the winery, meaning a winemaker does not have to be up at 2am to do a pump-over or plunge. Caldwell favours the very tech process of pigeage, or foot stomping, as a way of getting the best quality fruit from grapes. “That often produces some of our best wines with interesting characters,” he says.

Other innovations include the increasing use of biodynamics (although the science has been questioned); while organic farming focuses on limiting synthetic inputs, like chemical fertilizers, biodynamic farming looks at the farm and surrounding land as an ecosystem to determine the best ways to control pests and get the best yields.

Essentially, biodynamic farming uses organic methods, but is more big-picture focused, treating the land and the farm’s micro-climates as living things that need to be nurtured. Other advances may be of dubious benefit. While not yet as common as the wine cask (an Australian invention) canned wine is another packaging innovation that’s changing how we consume wine.

Other innovations include the increasing use of biodynamics (although the science has been questioned); while organic farming focuses on limiting synthetic inputs, like chemical fertilizers, biodynamic farming looks at the farm and surrounding land as an ecosystem to determine the best ways to control pests and get the best yields.

Essentially, biodynamic farming uses organic methods, but is more big-picture focused, treating the land and the farm’s micro-climates as living things that need to be nurtured. Other advances may be of dubious benefit. While not yet as common as the wine cask (an Australian invention) canned wine is another packaging innovation that’s changing how we consume wine.

Australian company Barokes developed and sold the first wine in a can in 2003, and the trend is now moving apace. Like bag in a box wine, one of the significant benefits with canned wines is that the finished wine’s oxygen exposure is limited. Cans also weigh less than glass bottles, which means a lower carbon footprint for shipping.

The use of screw caps rather than unreliable corks is now the norm in 95% of wines from Australia and New Zealand, while others have looked at the Vino-Lok glass stoppers, a German innovation.

The use of screw caps rather than unreliable corks is now the norm in 95% of wines from Australia and New Zealand, while others have looked at the Vino-Lok glass stoppers, a German innovation.